art jarvinen

art jarvinen art jarvinen

art jarvinen

Art Jarvinen (1956 - 2010) was a musician and a composer. He was in an early incarnations of John Trubee's The Ugly Janitors Of America (along with Jack Vees, Chas Smith, MB Gordy, and others), was part of the E.A.R. ensemble, and also used to be a music copyist for Frank Zappa.

The picture on the right is taken from his website: www.arthurjarvinen.com

in memoriam art jarvinen:

interview by John Trubee

October 2007

John

Trubee: When and where were you born? Where did you grow up? Could you

describe general impressions of your formative years?

Art

Jarvinen: Ilwaco, Washington, 1956. Moved around whenever my dad was called

by God to go to yet another shitty town. Kettle River, Minnesota. Eben,

Michigan. Port Arthur, Ontario. Warren, Ohio. All shit-drags. My youth was

characterized mostly by boredom, and trying as hard as I could to be saved,

probably to please my dad. The joke was "Art went up for the altar call

again". My dad's idea of a summer vacation was to take us to Bible camp. He

fished and hunted, but never showed me how. So I did things like read chemistry

books and learn how to make nitroglycerin. Mine didn't actually explode, but it

did go off when I threw a rock at it. Huge billowing clouds of orange smoke

spewing forth everywhere. I was so excited I immdiately mixed up another batch.

I stepped back and it went off spontaneously. My dad should probably have taken

me fishing.

John

Trubee: When and how did you get hired by Frank Zappa to do music copying

for him?

Art

Jarvinen: 1981. He had just fired Adam Stern because he wasn't producing

enough work to earn his salary. David Ocker suggested that I submit a work

sample, and I was hired immediately. He already had three full time salaried

copyists, but needed more staff because he was not only in heavy production, but

also still re-working things like 200 Motels. I was in Frank's employ for 14

months until his accountant told him he couldn't afford to be pumping that much

money into his "classical" work, which wasn't bringing money in.

John

Trubee: Did he also hire you to transcribe his music? What tunes of his

did you copy and transcribe?

Art

Jarvinen: I never transcribed. Steve Vai did almost all of that, and Richard

Emmett did some. What I did was what I guess you'd call "arranging".

Specifically, I took most of his orchestra scores and worked them out so they

could be played on two pianos. That's a common practice in the classical realm.

Stravinsky, for example, did his own two piano reduction of The Rite Of Spring.

I

copied those arrangements, plus things in the Frank Zappa Guitar Book. Not sure

which ones. Pink Napkins I remember.

John

Trubee: Your music copying work is remarkably clean and elegant. When,

where, and how did you learn to do it?

Art

Jarvinen: The specific technique you're referring to was developed by Donald

Martino as far as I know. He taught it to his students at Yale, including

Stephen "Lucky" Mosko, who taught it to several of his students at

CalArts. All the Zappa copyists who were working for him when I was hired were

trained by Lucky in that specific type of copying, so unless you have a real

good eye, you can't really tell our work apart. Sometimes we would get

reassigned mid-piece, and someone else would pick up where we left off. You'd be

hard pressed to tell.

But

now you couldn't get me to copy by hand for any amount of money. I only use

computer. Score and Sibelius. You couldn't pay me to use Finale either.

John

Trubee: What initially inspired your interest in music? How did you get

into music and at what age?

Art

Jarvinen: My family had a set of 45s with a song about every instrument of

the orchestra. When I was just starting out in grade school I listened to them

all the time, and always played Peter Percusssion several times in a row. I

didn't listen much to Lady Harp. More on that later...

But

then I heard the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan show, and said to myself,

"That's what I want to do". In second grade there were these cute

girls who were Beatles fanatics, and during recess they would put on their

records - I Want To Hold Your Hand, I Saw Her Standing There, that era, when the

songs had just come out. The girls would pantomime being John, Paul and George,

and I pretended to be Ringo. So I got to play Beatles with the girls while the

other boys played baseball or whatever it is that boys that age do. Did I miss

out on anything fun?

Anyway,

when I was in college this composer came to Ohio University as a guest. I had

never heard of him, his name was Alec Wilder. Only later did I learn he was the

guy who wrote Peter Percussion and

all those other songs I grew up with. I was really disappointed I hadn't known

that when I met him.

John

Trubee: What instruments do you play? Did you take lessons or were you

self-taught or half and half?

Art

Jarvinen: My bachelors and masters degrees are in percussion performance,

but I was self-taught until I went to college. Drum set to start with, then

mallets and most western classical instruments. Except timpani, which I had to

learn in college, and quit playing as soon as I could. I play no hand drums or

Latin stuff.

Everything

else I taught myself, including composition. Flute for six years, but not since

college. I could play all the Jethro Tull stuff in high school. I'm the world's

worst big band drummer, so I didn't really make it in the college jazz ensemble,

but all the wind players sucked on flute and could barely solo, so I was this

special sideman who came out to play flute parts and take solos. It was pretty

weird, a percussion major being the improvising flute player in the O.U. jazz

ensemble, as a freshman.

Electric

bass is now my primary instrument, which I started playing seriously in college,

on fretless. I would never play a bass with more than four string on it, in

fact, I wouldn't let you bring one in my house.

Slide

guitar, but no lap style. I have a National Triolian ca. 1930, and model my

technique and style mostly after Johnny Winter's acoustic slide playing, except

I wear the slide on my ring finger. Chromatic harmonica, which is all I use for

blues - most people don't seem to realize how many blues players play chromatic,

and seem to think it can't be done. I've also played a lot of composed

contemporary music on the chromatic, especially when the piece is not

orchestrated, so I can choose what I want to play.

Guitarron.

It took me years to find a good one, because even the best ones are shitty. Mine

is the best piece of shit I could find. I could tell just by looking at it, so I

traded a Fender Precision for it at a pawn shop, without even trying the

guitarron first. They're a bitch to amplify. I don't play upright bass, so I use

it when I want an acoustic bass. I played it in a Balkan music band for a couple

years and it fit in very well in that context.

I'm

a good singer for certain styles, including an excellent Brian Wilson falsetto,

and overtone singing. This is all stuff I do at a professional level. Now I'm

hardly ever performing, and am playing mostly banjo, frailing style, NOT

bluegrass. I have no interest in that kind of flash and don't much care for the

music. I like the Appalachian clawhammer stuff. Banjo's the first instrument

I've ever tackled that I have no plans to use professionally. It's my backyard

instrument, just for fun. I'm trying to see how many of my favorite songs I can

play on it in open G. I've got Pinball Wizard down, and The Shaw Sleeps In Lee

Harvey's Grave, by the Butthole surfers. I do those with Travis picking, which

you taught to me via e-mail as you may recall. It's funny to hear those songs

rendered in a mountain banjo style.

I've

also worked up a nice clawhammer version of Beefheart's "Orange Claw

Hammer", which as you know has no instrumental parts. Incidentally, I once

sang Orange Claw Hammer in a hotel lounge on an impromptu "cabaret"

style performance by the E.A.R. Unit in Helena Montana.

John

Trubee: What inspired your obsessive interest in surf music?

Art

Jarvinen: When I was a kid living in Port Arthur Ontario my brother got a

novelty album by The Silly Surfers. That's when I first started learning terms

like hodad and gremmie. I heard the Beach Boys' Surfin' USA, and also got

addicted to Good Vibrations. And I always enjoyed those stupid beach movies with

Annette and Frankie. Still watch them actually. Eventually, that's probably what

led me to find out about real surf music, but I don't remember just how when or

where. The Pyramids played in one of the Annette and Frankie movies. I don't

think they played Penetration though, which is the only tune they're known for.

It's

so weird that I can't really answer that question. I remember my house mates and

I had a "beach party" at our place in Newhall about 1982 or 83. I had

a Dick Dale album by that time, but I don't think I had much else. I think

probably in the mid '90s I started to seriously explore the genre via lots of

compilations. Surf music wouldn't even exist without the compilation album,

since most of the groups only had one song, and if they had more than one, they

still only had one good one. Dick Dale, by the way, is the only real

"name" in surf music, and by far my least favorite.

By

the way, did you know that the "little bit of surf music" on We're

Only In It For the Money is the opening of Heavies, by the Rotations. Only thing

is, the Rotations weren't a real group. Lots of surf music was just some guys in

a studio making a single. That was Frank playing guitar in exchange for studio

time before he bought out the owner of Studio Z in Cucamonga. At least that's

what I've read, and it makes perfect sense. The guitar playing is too good for

most surf bands.

John

Trubee: How does surf music manifest itself in your own music?

Art

Jarvinen: Well, in the last five years I've been writing shit-loads of surf music,

or things very inspired by it, for my web-based project The Invisible Guy. Given

how many surf tunes I've written, I feel confident in proclaiming myself the

most prolific surf composer ever. So, it manifiests itself in my music in that I

write surf music. When I'm not writing surf music, I am influenced by other

things.

John

Trubee: What instruments do you own and why? Any interesting stories

about how you acquired them?

Art

Jarvinen: I'm an instrument junkie. I just love instruments. Some years ago

I was invited by a New York composer named Phil Kline to contribute a cover

version of any pop tune that was on the radio in my lifetime, for a concert of

covers he was putting together for the New Museum. I did Tubular Bells with

every instrument or family of instrumnts I owned at the time. There were about

40 tracks.

2

marimbas, tuned bell plates, tuned cowbells, glockenspiel. etc. Lots of pitched

percussion. 2 Hammond organs, Hammond SoloVox. Boxes full of harmonicas. Many

guitars of various types. Bass, guitarron, flute, a consort of recorders,

electric keyboards, didjeridoo, baby grand piano, Chinese musette, jaw harps,

etc. I only used pitched instruments on Tubular Bells. I have a nice Gretsch

drum set, various gongs, an octave of turtle shells, Tibetan bowls, etc. etc.

I've

gotten rid of some things since, and have acquired others. Gave away a Hammond

organ, but Jack Vees is giving me his digital Hammond. When I get that you can

have my A100 if you want it, but you probably don't have the space. I gave the

pedals to Chas Smith recently. Sold

one marimba, and have the other one for sale. Started buying a lot of guitars. I

don't play real well, but I use them for learning about the guitar, and for

recording, and the guys in my surf band use them so I can have the sound I want.

Just

gave away a Fender Rhodes too. I have a Deering Good Time banjo and a hand made

Appalachian style fretless banjo.

Got

a bunch of amps. Etc. The stuff comes and goes, but there are always a lot of

instruments close at hand. It

depends on what I need at the time, and what interests me for whatever reason.

Depends too on what you might consider a musical instrument. I have a ton of

guitar effects pedals, but I've never plugged a guitar into any of them. I hook

them up to each other to create internal feedback, as a kind of crude analog

synth when I do live electronic music. I also have 5 shortwave radios, which I

use as instruments. Of course you can also just listen to them!

And

I recently got a Geiger counter, which I am looking forward to exploring the

possibiities of as a sound source.

John

Trubee: Please recount the saga of the

Hammond Solovox.

Art

Jarvinen: The SoloVox is a

thing of great beauty and wonder. Only made briefly in the 40s. It's a three

octave mini keyboard sort of like a Casio VL-Tone, hooked up to a box full of 18

tubes that are responsible for the oscillators, frequenciy dividers, timbral

controls, everything. All tube circuitry, and really weird, as are all Hammond

designs. The SoloVox is the instrument on the "organ" solo on Del

Shannon's Runaway. I got two of them on E-Bay. One of them I couldn't get

working, so I sent it to Jack Vees, whose dad fixed it, and it's currently

living in the electronic studio at Yale. The second one I got works, and I've

used it on several recordings. I won't part with that for a while. It's just too

cool.

John

Trubee: What are the titles of some of the many pieces you composed, for

what type of ensemble, and for what purpose? Fun? Commissions? A bit of both?

Art

Jarvinen: I caught a wave of good fortune in the '90s and had some very nice

commissions, but it's been pretty damn lean for some time now. The L.A.

Philharmonic doesn't tend to commission a lot of surf music, and even the more

"artsy" crowd, I think, sees me as more "classical", if they

see me as anything at all. My work is too diverse to build a good career on. So

I compose mostly for free, because it's the thing I enjoy doing most in life.

Some

titles? Jeez, Trubee, I have 80 chamber music pieces, 50 surf tunes, songs.

Where do I start?

The

Fifteen Fingers Of Dr. Wu. That's an oboe solo. I heard a voice in my sleep that

said "The name of this dream is The Fifteen Fingers of Dr. Wu". So I

named a piece after it.

Philifor

Honeycombed With Childishness. That's a chapter in a book by Witold Gombrovicz,

Ferdydurke, that I used for my L.A.

Philharmonic New Music Group commission.

I

borrow titles sometimes, like The Seven Golden Vampires, for two pianos. That's

from a kung fu/vampire movie.

Mostly

I get my own titles. I like them to be poetic, not descriptive like String

Quartet No 2 or Sonata.

Tribal

Songs of the Andromeda, Electric Jesus, Soluble Furniture, Erase the Fake, Clean

Your Gun, A Conspiracy Of Crows, White Lights Lead To Red

I

keep a file of good titles I think of even before I know what they'll be, if

anything. My latest title is Mining Clouds. No idea if I'll ever use it.

Fragments

Of God. That's another one I like that I do have plans for, but haven't written

yet.

John

Trubee: What work or works did you compose of which you feel the

proudest?

Art

Jarvinen: I am extremely proud of what I accomplished with The Invisible

Guy: a real soundtrack for an imaginary spy film. It's 50 tunes, all of which I

think are very good, some great, and every piece has a story/scene that goes

with it, and I think the writing is as good as the music. Plus it's all on line

and works real well as a web site. So it's a very rich artistic/entertainment

experience of substantial proportions. Problem is, when you spend four years

working on something like that, it's easy to be forgotten by the "new

music" community, and surf tunes don't really make it as current work

samples for the Guggenheim Fellowship Application. I also think Nighthawks is a

very special piece, but it falls in the cracks. Not "new music", not

"pop". I don't know what it is, and if I don't, makes it rather hard

to tell anyone else what it is.

Recently

I've been working on a set of pieces for male chorus a cappella. Never wrote for

voice before, but my first time out this incredible group from San Francisco,

Chanticleer, premiered the first six songs, including a performance at the

Library Of Congress. I feel rather proud that one of the best vocal ensembles in

the country would take on my first choral works. I must have a knack for vocal

writing.

I

also like my Three Tangos, for string quartet. They're good tangos, and good

quartets. Can't get anybody to play them though. They're not

"classical" enough, and they're not "new music" enough. I

just don't compose the right way I guess. Not to have a career anyway. For

example, I might very well be the only contemporary composer alive with

absolutely no interest in writing for orchestra. Orchestras sound weird to me.

Although if you offered me 25 grand I would certainly write you an orchestra

piece. I'm sure I have a good one in me, I just don't have any real need to

explore that territory, and wouldn't want to go there very often even if the

work was available to me, which it isn't.

John

Trubee: Which of your works most successfully conveys the musical meaning

you were attempting to express, and why?

Art Jarvinen: I can answer that best in the negative.

I

don't generally have what I would call "meaning" to express. I have

ideas to express, compositional ideas, musical ideas. That's not the same as

meaning.

I

had a very prestigious commission from the Koussevitsky Music Foundation in the

Library Of Congress, in 1990. Composers like me aren't supposed to get those

things, and a lot of composers who regularly get those things are jealous of me

because I got one and they still haven't. I know this because they tell me so.

I

had been working with a particular technique I developed that turned out a

number of really cool pieces. But I saw that it could become a habit or a style,

something I could do too easily or default to, so I wanted to push the idea to

the breaking point such that I could never go back to it and would have to find

something new. So I wrote a piece called The Modulus Of Elasticity, which is a

materials enginering formula for determining things like how tall you can make a

steel pole before it collapses under its own weight. I pushed those ideas to

their breaking point. It's the weirdest piece I've ever written, and not one of

my best. But I'm proud of it because it did what I needed it to do, which was

make me move on instead of kicking back in a creative comfort zone.

Then there's A Conspiracy Of Crows. It's a piece for three oboes in which I didn't consciously choose or compose any of the notes. I just used a series of numbers based on the years of the 20th Century - 190019011902...1999 - translated into fingering diagrams. I had no way of knowing what would come out, but I had a very good idea of what I thought the piece would "probably" sound like. I never heard a note of it until it was recorded here at my house last summer. It's one of the most beautiful things I've produced, and it fully matched my expectations. My wife is almost frightened by things like that, that I can intuit or anticipate these things. That's why I'm a composer, and some people aren't.

In

2002 I had a City Of Los Angeles Artist Fellowship to compose and present a

piece called Nighthawks, a song cycle based on Edward Hopper paintings. It's

very autobiographical, something I thought I would never do. Some people have

told me it's maybe my best piece, certainly on the short list, and I tend to

agree. I think it works because it conveys rather powerfully a meaning that I

did not foresee or plan to express. Once the pictures started speaking to me,

the piece took over and I trusted it. That's one of the only things I've done

that carries both musical meaning and intention, and also has a very real

personal "message", my story if you will.

John

Trubee: Describe your association with the Grandmothers.

Art Jarvinen: I wouldn't call it an association, not musically or professionaly anyway. I am close friends with Chris Garcia, the drummer, and Miroslav Tadic, the guitarist. I am also friends with Don Preston, although I wouldn't say I know him real well, but we get along very well and have worked together several times. That's always a treat. Don is a wonderful guy and musician. I like Roy Estrada a lot, but only met him fairly recently. Although I heard him recording No Not Now at Frank's studio, and thought he sounded great. But Frank replaced Roy's parts with his own voice - not nearly as interesting or fun. But then, neither is the song.

Sometimes

Chris calls to see if I have music for certain Zappa pieces the Grandmothers

would like to do. I transcribed Project X for them, which was a bitch, but I did

it because I was always interested in that piece anyway. I have no idea if

they'll ever use the transcription. Chris sent it to Art Tripp, who I'm told

gave it his seal of approval. Too late to ask Frank how close I got.

John

Trubee: Would you be willing to recount your drunken Danny Elfman story

for our readers?

Art

Jarvinen: That was for your amusement. I don't know Mr. Elfman and have no

reason to embarrass him or get him mad at me. He was just falling down drunk at

his own party, Who hasn't done that? Okay, you, but you're maybe the only one.

I've certainly been plenty blotto on numerous occasions. The main point of that

story was the part about the jerk who was feeding a whole platter of those

incredible lamb loin chops to the fucking dog! That kind of careless decadence

offends me. Not only was it an incredibly stupid waste of very expensive food,

it was unhealthful for the dog. That idiot should have been taken out back and

caned. And that guy wasn't Elfman, I don't know who he was.

John

Trubee: Got any other funny or weird stories that you wish to immortalize

here for posterity?

Art Jarvinen: FZ related? Funny and weird don't leap to mind, since I wasn't around him that much and wasn't in the band. Funny and weird would be road stories I would think. I have some nice stories. After Frank heard the piano reductions for the first time Gail called me and said she thought I'd like to know, since Frank would never tell me himself, that he was blown away by them, and was prancing around the house with glee. She was right, he never said anything to me about them. And a few years ago I met Bob Rice, Frank's engineer, who introduced himself and said that I was the only person he could think of that Frank only had good things to say about. That sort of thing is gratifying to hear once in a while.

Apropos

my orchestra comment above, I was at Frank's when he was working on his string

quartet for the Kronos. He played me what he had so far on the Synclavier, and

it was set up with these huge lush orchestra sounds, nothing like a quartet. He

was very frustrated with the piece and said, and I quote, "You can't do

anything with a string quartet". I thought, gee Frank, I know some guys

named Beethoven, Brahms, Bartok, Ives, etc. who might disagree. Frank had no

interest in writing that piece. He wanted to write an orchestra piece. I think

he took the Kronos commission for the money, and because he was looking to gain

some credibility as a "classical" composer. He tried to get the Kronos

to release the piece in two versions on one disk, the acoustic quartet, and the

Synclavier version. They wisely refused.

As for the Roy Estrada recording sesssion mentioned previously. Frank had him

singing "But I like her sister" in Pachuco falsetto over and over

again. Gail came in and said "He sounds real out of tune". Frank said

"He always does, but it's such a great sound!". I think he was just

digging listening to Roy's voice. As I said, he never even used the track.

John

Trubee: Frank Zappa once helped you with some of your inquiries regarding

compositional techniques.

Art

Jarvinen: Did I ever say that? I don't recall ever asking him about his

technique, or about composition. I've been real curious about his "chord

bible", which was a sort of automated way he had of harmonizing his

melodies. But I heard about that from David Ocker. I'm hoping to reverse

engineer some of the logic of the chord bible, but haven't gotten very far, not

far enough to determine whether or not I think it's even possible. But now that

I know it existed, I can see it all over the place in the score to Sinister

Footwear. I just don't know its internal logic. I wish I had known about it when

I worked for Frank, because I would have certainly asked him about that, and I'm

sure he would have enjoyed telling me about it.

That gets back to the Kronos quartet. Frank was working with the seven note

version of the chord bible then, and using very thick harmony. I think he was

frustrated with the quartet as a medium because he couldn't write densely

enough, which is what he was into at the time. Thick harmony, big fat melody.

John

Trubee: You told me he was very generous with his time. Wanna tell our

readers about it?

Art

Jarvinen: Whenever I went to the house to drop off or pick up some work, he

was always willing to spend some time talking to me, let me hang out and watch

recording sessions, gave me the sandwiches that Gail sent down for him. Stuff

like that. He just made me feel like I was welcome there, and not in the way.

When he got the Linn drum machine he insisted that I try it out. When Midget

Sloatman was installing some custom electronics in his Les Paul I got to sit

there and listen to Frank try it out. He let me hang around when the Simmons

electronic drums rep came over to demo the stuff. Frank had me sit down and play

the kit for a while and said "Wadda ya think?" I said "Real

futuristic. I dig the fins".

I remember that event because the

Simmons guy couldn't get the snare pad working right, and kept fucking around

with it, and couldn't get it right, but kept assuring Frank that it really

sounded great and was really cool. Then he gave up and admitted he wasn't a

technical guy, just a sales rep. I thought Jeezus, what idiot sent a SALES REP

to demo ELECTRONIC MUSIC EQUIPMENT to FRANK ZAPPA?

John

Trubee: Tell our readers about your long association with the California

Ear Unit and describe the work of that ensemble to our readers, please.

Art

Jarvinen: They asked me to join about three times before I finally did. I

wasn't that interested in the repertoire that they were doing in the beginning.

Once I joined I had a lot to do with bringing programming ideas to the table,

and I think the most interesting thing about the group is the amazing diversity

of repertoire that we did, because we all had different things we were

interested in. You can't show me another ensemble on the planet that covers the

territory we did over the years. The group is still together, but I left about

seven years ago. Eighteen years was enough. There was nothing left for me in the

group at that point, and they haven't done anything since that made me wish I

was up there playing it. Nothing new has happened in a long time, whereas for

most of the years I was in the group we were usually doing things that were

either very fresh at the time, or a stretch for us at least.

We played a lot of festivals internationally, premiered tons of stuff, had lots

of cool pieces written for us specifically, and worked with many of the most

important composers of our era. Especially due to Bang On A Can we were maybe

the only - certainly on a very short list of - west coast groups to play any

active role in the Downtown New York scene when it was still evolving. But

because we could play Carter and Babbitt and all that stuff too, we also worked

Uptown.

Usually

in L.A. Dorothy would wear things like a mini skirt with six guns on it, Amy

would wear rubber skirts and cowboy boots, and I'd have on a white dinner jacket

and a Fez. Some reviewers talked more about our clothes than the music. Then we

did this gig at Columbia University, and the girls all transformed completely.

Nice dresses, tasteful jewelry, no glitter in their hair. But all the pieces on

the first half had nocturnal themes and titles, so I wore pajamas and a night

cap. The girls took Jim Rohrig, the clarinetist aside in the green room and said

"Can you get Art to not wear that? We can't talk to him, but maybe you

can". I wore the pajamas anyway. They were embarrassed because they wanted

to impress the Uptown people. I thought it was hypocritical to change your style

to try to please an audience, especially based on assumptions that might not be

valid. What if they had hired us expecting us to be the group they had heard so

much about? What if they wanted to see the rubber skirts and glitter? Maybe we

disappointed them.

I played bass a lot in the group, and I have a pair of "shiny bimbos"

- those ridiculous silver ladies that you see on truckers' mud flaps - on my

bass. Still do. They were always embarrased by that too, and sometimes asked me

to position myself on stage so they wouldn't be noticed. So I got a long cord so

I could wander over to the edge of the stage while playing and face the

audience. I got a large pair of shiny bimbos that I planned to put on my marimba

resonators, but never got around to it. Nick Didkovsky just wrote to me asking

me where you can get them, so I sent him that pair. He said they're kind of a

hot item now. Not sure what that means. Maybe I should have sold them on E-Bay,

but I'd rather give them to Nick.

Don't get me wromg, I love the E.A.R. Unit women. But I did sometimes do things

just to piss them off or embarrass them, especially if I thought we were selling

one image to one audience, and pretending to be something else for a different

audience. I thought we should be honest, and just be ourselves.

John

Trubee: What was the coolest gig you ever played, and why?

Art Jarvinen: I don't know if I'd say it was the "coolest", but one of the most memorable performing experiences was when the E.A.R. Unit played at SUNY Buffalo. We played a mother-fucker of a hard piece called Notturno, by Donald Martino. Hard core 12 tone stuff, and I had a huge set up, every lick was hard to play, and I had about fifty mallets and sticks and was changing them almost every phrase. Most players split up the part between two percussionists, but I did it myself, as written. I remember that performance because as we were playing I would make my page turn, change my sticks, and get ready for the next hard lick - and wait. All the stuff I had been scrambling for was just right there, like the piece was happening in slow motion and I was way ahead of the game. It was a great feeling to know a piece of music that well, especially since at that time the E.A.R. Unit was learning about 30 or 40 new pieces every season, and playing most of them only once or twice.

As

for the "coolest", to actually answer your question, it would have to

be the time the EARs played John Cage's "Lecture On the Weather",

which starts with a lengthy preamble that Cage requires be read before the piece

proper. I called him from the L.A. County Museum at his home in New York and got

him to read it himself live over the phone. That was very generous of him,

because he was in frail health at the time. The L.A. County Museum wouldn't

authorize us to have an outside line for the concert, so I had to tap a back

stage phone. That was cool.

John

Trubee: Was 'When You Were Art' dedicated to you?

Art

Jarvinen: I wouldn't say "dedicated". The title does refer to me.

It's actually "While You Were Art". A slight change on "While You

Were Out", which is a piece on the Shut Up And Play Your Guitar set, that

Frank arranged and reworked for the E.A.R. Unit at my request. No money changed

hands.

John

Trubee: Please describe the fiasco surrounding the first public

performance of the piece by the Ear Unit at LA's Bing Theater.

Art Jarvinen: I am STILL getting asked about that, and it was 1984 I think. Every once in a while I sit down intending to write the definitive account as I know it, once and for all, and post it on-line so I never have to tell the story again. Basically, as far as I can tell, Frank never did intend to give us a piece we could actually play. We could have played it, and intended to eventually, but he delivered it late enough that we could not possibly have learned it well enough in the time left before the scheduled performance. So he asked us if we would be willing to "lip synch" it. And we said yes. Then several people got cold feet, but we did it anyway. It was no big deal for people who could hide behind their instrument or music stand, but I busted my ass for almost a month to learn that marimba part, and played it with foam rubber mallets. I was actually playing the part, but you couldn't hear me. I had no choice, because if the marimba is near the edge of the stage in plain sight, you can't pantomime playing it.

Anyway,

Frank himself leaked the secret to a reporter during a flight, so I'm told, and

the shit hit the fan. That would have been such a great opportunity for all

kinds of critical dialogue, not to mention great publicity. We could have

programmed the piece on lots of concerts so audiences could see for themselves

what we had puled off. But the E.A.R. Unit has worked a lot with Morton

Subotnick, and several people in the group at that time were particularly close

to him. Mort was very upset by what we had done, and some people were made to

feel very ashamed. So when a reporter from the L.A. Times called CalArts and

wanted to talk to someone in the E.A.R. Unit about While You Were Art, they got

the "wrong" person on the phone. Had they talked to me, history would

have unfolded differently. Instead one or two people in the group put their

tails between their legs and basically apologized for the error of our ways, on

behalf of the group. That pissed me off, but Frank was livid. He called me and

said we could never play his music again and made me send all the material back.

I assured him that the sentiment expressed in the newspaper article was not a

group consensus, so he said I should tell that to Time Magazine, who had just

interviewed him about the event. But Time never called, and I don't think they

even ran the article.

There's more to the story, but that's the basic plot.

John

Trubee: What do you really hate, and why?

Art

Jarvinen: Rap and all its derivatives, because to me it is ugly and stupid.

John

Trubee: What do you really love, and why?

Art

Jarvinen: Thai food, because it's delicious and when I first tasted it I

felt I had found my way home.

John

Trubee: What's your favorite color?

Art

Jarvinen: For clothing, black. For anything else, no favorite.

John

Trubee: What's you favorite flavor of ice cream?

Art

Jarvinen: Green tea. That and ginger are the only ice cream I will eat, and

those infrequently.

Art Jarvinen promised John Trubee some pictures to go with the interview. As every picture came with a bit of explanation, I'm adding them like this:

| Here's a pic of a very nice piece of gear, very dear to my heart. The SURB is a tank reverb, all tube, hand built and given to me by Miroslav Tadic. It's based on the Fender spring reverb unit, but with several significant improvements. Note the little surf board on the front, and all the woodwork was done by Miroslav too. Even without an amp, you go through this and into a direct box and you've got a great surf sound for recording. |  |

|

Here

are the electric guitars I've been using. None

are vintage. The Tele was a Japanese reissue Esquire that I added the

neck pickup to. Miroslav added the Bigsby for me. I'll take this one to

my grave. If I could only have one guitar, this would be it. The

Jag is an American reissue of the '62. The original Jaguar was a piece

of shit, especially the bridge, so of course the reissue is too, in

order to keep it authentic. It seems that only perfect things like Coca

Cola get "improved", which always ruins them, but things that

could use some real work stay the same. Go Figure. The guitar does sound

good when it's in tune, which isn't often, but the tremolo simply can't

be beat for surf music. I'd miss that a lot, but I would trade this

guitar straight across for a Taurus PT92 9mm semi-automatic. The

baritone started life as a no-name "Strat-Type" that I got for

$40 at a Sears outlet store. I had Miroslav do the work on a Stew/Mac

neck, so it plays real nice. The pickups are for shit, and I have some

better ones but haven't put them in yet. The

Ric 12 string is 21st Century, bought new at Guitar Center in L.A. They

warned me that they thought it was fucked up because they couldn't get

it in tune. It's beautiful. Someone there just can't tune a 12 string.

George Harrison once said that the great thing about the Ric 12 is that

you can even tune it drunk.

|

|

|

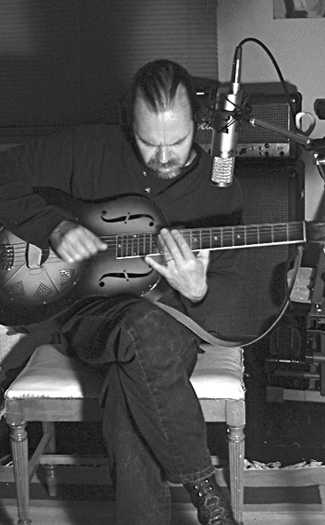

| Here's me recording my song "Warren",

which to be honest is just a reworking of Johhny Winter's

"Dallas". It's on my CD Pailface, Blues Singer, with Miroslav

Tadic as Midget Waterslavsky.

The album is mostly a loving parody of Muddy Waters, Folk Singer, one of the most beautiful records of all time. We did this record in one take at Miroslav's house a few years ago. That's my 1930 National Triolian. You always hear those stories about finding a National or a Strad or a Rembrandt or whatever in your grandma's attic. I hadn't seen this friend of mine in about ten years and he asked me what I was up to. I said I was getting into slide guitar and wanted a National. He said what's that and I said it's this metal guitar with a cone in it. He said, oh yeah, my uncle has one, stuck under his bed, never plays it. I went to Ohio and bought it for $450. |

|

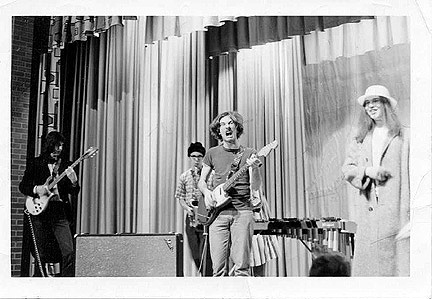

Dog Breath

Here's something fun. The guy on the right is me. That's my band, Dog Breath playing at the annual talent show at Warren Western Reserve High School. Except for Roland Kirk's "Serenade To A Cuckoo", which we did in the Jethro Tull version and featured me on flute, we played nothing but Zappa material. You gotta remember, this was 1972/73. There were no such things as tribute bands, and we weren't pretending to be the Mothers. All we wanted to play was Zappa, and that's all we did. We had to lift everything off the records, so I can't vouch for the accuracy of the charts, but what we played we played pretty well.

|

The

pieces I remember us doing were:

We probably did It Can't Happen Here. We didn't do any real gigs, only played at our school, but we did get engaged to play a dance in the gym, and I tell you what, the kids were NOT happy. They just stood there staring up at us. Fortunately we were isolated up on a balcony. No one danced. I think they were waiting for I Wanna Make It With You so the jocks could get in a slow dance with a cheerleader. No such luck, Macho Boy! Ha Ha. |

|